A survey of the global economic landscape reveals the contours of an uneven recovery from the pandemic-induced recession. The global economy is undergoing a transition from a re-opening mini boom earlier this year to a resettlement period of slower but still above trend growth into 2022.

The two largest economies – the US and China – are at different phases of retreat from emergency macro policy settings, while improved global vaccine penetration is gaining on the latest viral wave. Supply chain disruptions linger across the global manufacturing and energy complexes, however, causing price gyrations in everything from cotton to semiconductors to container shipping rates.

The upshot is an unsynchronized global economic backdrop creating a wide cone of uncertainty around the outlook for inflation, interest rates, and equity markets. Evidence that macro policy will become more stimulative in China and not tighten too quickly in the US is a prerequisite for investors to gain conviction that this secular bull market still has legs into 2022.

Chinese Currents

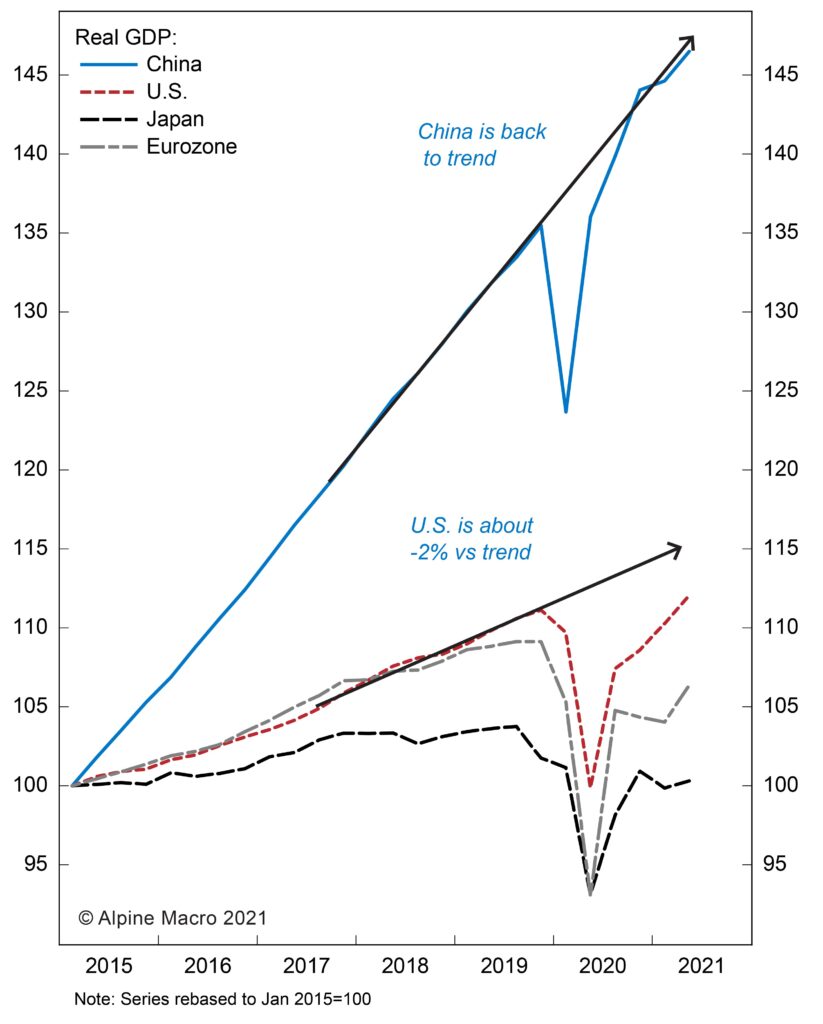

China was the first major economy to enter and exit the sharp but short-lived Covid shutdown and recession. The Chinese economy rebounded to its 6% trend rate of GDP growth this year, prompting policymakers to be the first to reverse pandemic-related economic stimulus.

The authorities quickly pivoted to a multi-pronged structural reform agenda which caused economic activity to slow sharply in Q3. A trifecta of policies underscores the risks to growth when politics collide with economics.

- A regulatory crackdown on the technology sector to reduce monopoly power and media reach that challenge the Communist Party of China’s (CPC) primacy;

- restricting the highly levered property sector’s access to bank credit; and now;

- an environmental campaign causing rolling electricity brownouts which risk idling large swathes of the energy-intensive industrial sector.

These initiatives do serve China’s longer term economic development and social stability objectives, which align, conveniently, with the CPC’s regime preservation reflex. Nonetheless, they raise the risk of the economy hitting an air pocket, if fiscal and monetary settings are not eased aggressively.

On top of taking heavy-handed regulatory action, China has a zero tolerance for covid, such that factories and retail outlets shut down and supply chains freeze in every city upon discovery of any outbreak, even though vaccination uptake has been high. Retail sales growth, manufacturing activity, and infrastructure spending are all weakening now, as a result. Moreover, credit growth, a key lubricant and leading indicator of overall economic growth, is contracting on a year over year, rate of change basis.

While similar in size to the US economy, China’s potential growth (6%) is about triple the US’s (2%), so its marginal contribution to global economic momentum is more meaningful, and the recent slowdown will be a drag on global aggregate demand.

The good news is that China is signaling awareness and willingness to address the recent slowdown. Monetary and fiscal policy should shift into a more pronounced, reflationary gear over the balance of 2021. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has pledged to support the housing sector and injected liquidity into the financial system to prevent financial stress related to the liquidity woes of the largest property developer, Evergrande, from spreading.

The bad news is that stimulus deployed now will take around six months to reboot the Chinese economy. In the interim, growth will continue to languish, which is bearish for global growth.

US Currents

The US fiscal and monetary policy backdrop is undeniably more stimulative than China’s. No G7 economy has provided larger fiscal subsidies to households as a share of GDP than the US. Financial conditions – bond yields, bank lending standards, and credit spreads – have also never been more pro-cyclical.

The wildcard for the next phase of America’s post-pandemic recovery is the labor market, a key driver of consumer confidence and spending, which accounts for 70% of economic activity. As of Labor Day, America’s pandemic unemployment insurance scheme ended. The September non-farm payroll report underscored that some five million American jobs are still ‘missing’ relative to February 2020.

The pace at which employment income supplants fiscal subsidies, and the willingness of consumers to spend that income will dictate the thrust and longevity of this business cycle. The Federal Reserve is watching closely. The evolution of labor force participation and wage growth will inform how quickly they normalize monetary policy.

In addition to labor market conditions, the Fed is keenly focused on what to do about current inflationary pressure building from the constellation of global manufacturing, shipping, and delivery bottle necks, labor shortages (in select sectors), and a budding global energy crunch. Importantly, none of these dislocations can be remedied by monetary policy, which is an economic lever for the demand side of the economy, not the supply side.

The old adage about commodity prices rings true, still: the cure for high prices is high prices, particularly when shortages are the culprit. Supply constraints that push up prices end up destroying demand in the process.

For this reason, and because a slower pulse of Chinese economic momentum is itself a deflationary shock for global growth, the Fed is unlikely to raise interest rates in response to what they still see as a transitory rise in the relative price of some goods and services.

Importantly, productivity growth has matched nominal wage growth. For this reason, headline stories about rising wages belie the reality that unit labor costs have been stable. This means that outside of sectors specifically (and likely temporarily) impacted by the pandemic, broad-based inflation pressure in the US economy has yet to take root. Long term inflation expectations are still well anchored around the Fed’s statutory 2% long term target.

Though US GDP growth peaked this summer as base effects from last year’s sudden stop in economic activity were amplified, the economy is still likely to grow above its 2% trend rate this year and next, because slack remains in the labor market.

Firms are in maximum efficiency mode, and while the corporate profit bonanza has peaked, earnings growth will remain positive as supply constraints abate and demand remains buoyant. Massive unspent household savings, healthy business formation, and strong household and bank balance sheets are all durable tailwinds for US growth even as macro policy stimulus recedes from maximum throttle.

The question for investors is what balance of macro risks do equity valuations already reflect? Through October 4th, 90% of S&P 500 and NASDAQ listed firms had already undergone a 10% decline from their recent highs. This pullback reflects the fact that markets are forward discounting mechanisms, and that the mini boom that characterized the economy’s reopening is shifting to a slower, albeit still positive trajectory.

China’s slowdown may cause commodity prices to drop and the US dollar to strengthen in the near term. This deflationary global pulse may give the Fed cover to maintain a permissive attitude towards current inflation trends and delay raising interest rates. As long as China’s policy mix turns more stimulative, quickly, and the US labor market continues to heal, corrective churn in markets through the middle of this year is not a game-ender for this secular bull market.

Caroline Miller

Caroline S. Miller is the Chief Asset Allocation Strategist at Alpine Macro Inc. She has served as a Director of the Pembroke American Growth Fund since 2019 and joined Pembroke’s Asset Allocation Committee in 2021. The views expressed in this article are those of the author.

LEARN MORE:

- See Our Solutions page for Pembroke’s range of funds.

- Learn about Pembroke’s Investment Philosophy.

- You can also Meet the Team here at Pembroke.

Other Articles Of Interest

Disclaimer

This report is for the purpose of providing some insight into Pembroke and the Pembroke funds. Past performance is not indicative of future returns. Any securities listed herein, are for informational purposes only and are not intended and should not be construed as investment advice nor is it a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security. Factual information has been taken from sources we believe to be reliable, but its accuracy, completeness or interpretation cannot be guaranteed. Pembroke seeks to ensure that the content of this document is correct and up to date but does not guarantee that the content is accurate and complete and does not assume any responsibility for this. Pembroke is not responsible for decisions or actions taken or made on the basis of information contained in this document.