How did a generation of price stability, moderate economic growth, and low interest rates give way to a spike in borrowing costs, and one of the steepest six-month drawdowns in financial markets since the mid-1970s? For the first time in a generation, inflation is the most pressing threat to our economic and financial wellbeing.

To understand how this economic imbalance came about, it is worth reviewing the macro policy backdrop at the outset of the pandemic. With the benefit of hindsight, governments often fight the last war when setting economic policy. The shadow of the 2008 Great Financial Crisis and the deflationary spiral that it sparked were still fresh in policymakers’ minds when the pandemic crisis erupted in March of 2020.

The Stimulus Hangover

As COVID forced the unprecedented shuttering of the global economy, the prevailing sense at the time was that the risk of governments providing too little support to consumers, businesses, and financial markets was far greater than the risk of offering too much. Little thought was given to the exit strategy from the ocean of debt-financed liquidity being unleashed on the economy as an indemnity against an economic abyss of unknown depth and duration. Fast forward to today: North American fiscal and monetary largesse has left us with a hangover, the primary symptom being inflation.

Conceptually, when demand for a good or service exceeds available supply, its price rises to a level that equilibrates supply and demand. The COVID economic sudden stop and ensuing macro policy response created just such a scenario. Bottlenecks throughout the manufacturing supply chain limited the availability of many goods, just as governments stimulated demand by putting money into consumers’ pockets and liquidity into markets as insurance against open-ended income interruption.

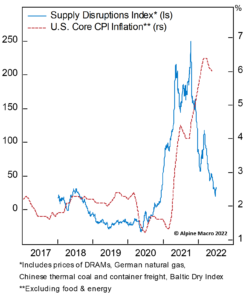

Russian and Chinese Supply Curveballs

As the global economy reopened, supply chain normalization was expected to reduce inflationary pressure. But in February, Russia invaded Ukraine, creating another supply shock across the commodity complex, and, in March, much of industrialized China went back into COVID lockdown, prolonging supply chain bottlenecks in the world’s factory. Supply chain normalization was delayed. While neither Russia’s naked aggression nor China’s draconian zero-COVID policy could have been foreseen, both aggravated global inflationary pressure that originated with government subsidies and central bank money printing.

Central Banks Are Behind the Inflation Curve

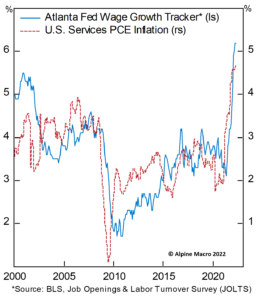

Pent-up demand for travel and entertainment has caused the goods spending binge to migrate to the service sector where labour shortages persist, pushing up wages, and reinforcing inflationary pressure.

On top of an overheated labour market, little residential construction took place for two years, while many bought second homes or upgraded their existing ones to accommodate hybrid “work from home” lifestyles. All this provoked a ubiquitous rise in the cost of shelter.

The upshot of all these imbalances is that inflation has soared from the 2% average that had prevailed since the end of the 2008 financial crisis to 7.7% in Canada, and 8.6% in the US today. Central banks were like frogs in water heating up slowly late last year. Now that the water is boiling, they have sprung into action, nursing burnt credibility.

Interest rate policy is a demand management tool. The cost of capital, which the Fed influences through setting the risk-free rate for short-term borrowing, has no ability to remedy inflation resulting from COVID or war-related supply shocks. For central banks, when all they have is a hammer (the interest rate lever), every source of inflation looks like a nail. Neither the Fed nor the Bank of Canada can adjudicate over an attribution of which sources of inflation they do or do not control as they form policy today. They must simply create enough slack in the economy to cool demand in order to bring inflation down.

Has Inflation Peaked?

There are signs that higher interest rates are starting to cool the housing markets in Canada and the US, while swollen wholesale inventories suggest that the consumer goods spending binge is grinding to a halt. The world’s factory, China, has reopened. The prices of global shipping, DRAMs (semiconductors), and lumber are all falling quickly.

Nonetheless, service inflation remains stubbornly sticky, owing to persistent labour shortages in many high contact sectors, such as hospitality, travel, transportation and logistics. The upshot is that core inflation may be peaking, but it will not drop quickly enough, organically, without more policy tightening. Cue continued interest rate hikes to create slack in the labour market, moderate wage gains, and break the back of demand-pull inflation, even as cost-push inflation is already dropping.

Central Banks Have One Job

Having been too slow to stop force feeding the economy when inflation was rising, odds are high that the Fed and the Bank of Canada will not stop tightening policy before the economy has experienced a significant slowdown, or even a mild recession. This is partly because of the inconvenient fact that monetary policy operates with a lag. Today’s rate increases will not slow economic growth meaningfully until later this year, or early next year. By then, financial conditions will have already tightened beyond the economy’s choke point, and inflation will be declining faster than expected.

What Happened to the 60/40 Portfolio?

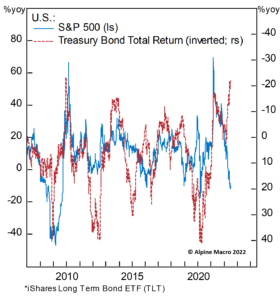

After the 2008 financial crisis, but before the COVID era, the clear and present danger for equity markets was deflation, the consequence of aggregate demand and economic growth being too weak. Then, bonds served as an effective ballast to equities in balanced portfolios. Periods of weakness for the equity portion were cushioned by gains in the fixed income allocation when stock market drawdowns prompted central banks to cut interest rates, which pushed up bond prices and revived stocks.

The Fed’s reaction function to markets has reversed in the wake of rising inflation. In the first half of 2022, stock prices dropped largely because inflation forced markets to discount a steeper path of interest rate hikes, causing price-to-earnings multiples to compress. Investors also sold bonds, anticipating that inflation will erode the value of long dated fixed coupon income. In short, bonds lost their hedging value for equity risk.

Have Financial Markets Discounted Enough Bad News?

The bottom of a bear market is notoriously difficult to time, but equity valuation and earnings growth markdowns suggest that the current sell-off is advanced. Future interest rate increases have been well advertised to markets, but have yet to filter through fully to the real economy. Global growth is slowing from its robust post-COVID reopening clip. Inflation is likely to be much lower by year end, as the economy loses momentum and supply disruptions abate. The war in Ukraine is a wildcard for commodity prices, but weaker demand because of slower economic growth is likely to dominate supply uncertainty over the near term.

Diversification Lives

If the prevailing risk to equity shifts from sticky inflation back to weaker growth, the correlation of stock and bond price movements will revert to its pre-COVID trend. By year end, bad economic news is likely to be good news for financial markets, which are forward-looking discounting mechanisms. A growth slowdown will signal the end of aggressive interest rate hikes, giving rise to expectations of a new monetary easing cycle in 2023. A balanced, diversified portfolio framework should reward investors with the patience to stay in their seats.

Caroline S. Miller

Caroline S. Miller is the Chief Asset Allocation Strategist at Alpine Macro Inc. She has served as a Director of the Pembroke American Growth Fund since 2019 and joined Pembroke’s Asset Allocation Committee in 2021. The views expressed in this article are those of the author.

Other Articles Of Interest

Disclaimer

This report is for the purpose of providing some insight into Pembroke and the Pembroke funds. Past performance is not indicative of future returns. Any securities listed herein, are for informational purposes only and are not intended and should not be construed as investment advice nor is it a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security. Factual information has been taken from sources we believe to be reliable, but its accuracy, completeness or interpretation cannot be guaranteed. Pembroke seeks to ensure that the content of this document is correct and up to date but does not guarantee that the content is accurate and complete and does not assume any responsibility for this. Pembroke is not responsible for decisions or actions taken or made on the basis of information contained in this document.